The Height Of Safety

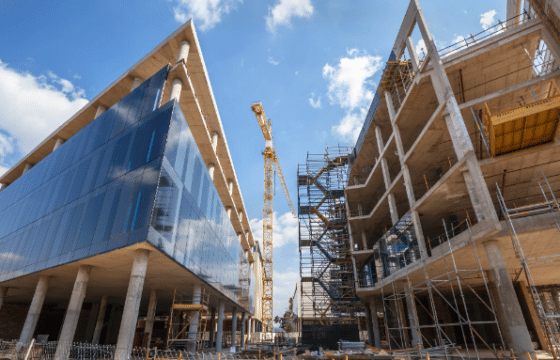

Working at height remains one of the greatest risks to the safety of HVAC&R technicians nationwide. And the incidence of falls continues to alarm, with Safe Work Australia reporting 51 related fatalities in the construction industry between 2007 and 2012. Sean McGowan reports on the dangers and solutions.

You may take working at height for granted, or look at it as just being part of the job. The adventurous among you might even get a buzz out of doing it.

But the reality is that working at height is seriously dangerous.

In 2011–12, every day 21 employees lodged a claim for a falls-related injury that required one or more weeks off work. A typical falls-related claim required 6.2 weeks off work.

And to hammer home the reality, over the five years from 2007–8 to 2011–12, falls from height accounted for 51 fatalities in the construction industry. Of these, 18 involved falls from buildings, 15 involved ladders and eight involved scaffolding.

These are the stark statistics offered by Safe Work Australia, a government-led body established by the Safe Work Australia Act 2008. Its primary responsibility is to lead policy development around the improvement of work health and safety, and workers’ compensation arrangements across the nation.

Carl Sachs is chair of the technical committee for the Working At Height Association (WAHA) and managing director of Workplace Access & Safety. He says service technicians who work at height are covered by workplace health and safety laws and Australian Standards, which are prescriptive.

In some states, the Standards are referenced in the codes of practice and regulations, making it mandatory to meet the requirements to the letter.

Even where they are not directly referenced, Standards can be used as evidence by workers or workplaces that they’ve met the requirements of the benchmark standard.

These include AS1657, which covers fixed walkways, platforms, ladders, guard railing and stairs for maintenance access. By being specified in the BCA, they are mandatory. Reviewed in 2013, this Standard grew from 32 pages to 100 pages, as added explanatory material and drawings made it easier to interpret.

Additionally, AS/NZS5532 was also released last year.

“AS/NZS5532 is the new manufacturing Standard for the anchors that HVAC&R technicians use to attach their lanyards and harnesses to rooftops,” says Sachs.

This standard spells out how manufacturers test the product, and the documentation that needs to accompany an anchor. Until it was released last year, manufacturers didn’t have a benchmark test method to prove their product was capable of saving a life.

“A really simple way to tell is an anchor is safe or not is to look for the StandardsMark – the five tick logo,” Sachs says, “or ask for test certificates from a NATA accredited laboratory.”

TYPICAL HAZARDS

The typical location of HVAC&R plant on rooftops naturally creates its own hazards to access.

Service points on cooling towers are often at some considerable height. Evaporative coolers and condensers can be located next to exposed edges of buildings, open voids, or next to brittle surfaces such as skylights, or even on asbestos roofs.

And although steep roofs present obvious challenges, even flatter surfaces can present a hazard.

“It’s equally important to consider how to reach the work area safely, and how you get your equipment up there,” says Sachs.

“Climbing up a 6m extension ladder with your tools in one hand and a gas bottle in the other isn’t safe or legal. Neither is climbing over parapet walls or jumping over skylights or polycarbonate sheeting.”

“Plan how to get to the service areas, not just around the units.”

Hazards, however, don’t just exist on commercial sites. Working on residential buildings also presents major risks to HVAC technicians.

Although there is a separate code of practice for working on residential premises at height, in practical terms similar measures need to be taken to stay safe.

“Whether a worker falls off a double-storey home or an office roof, the consequences for that person are the same,” says Sachs.

“My personal experience is that while getting the message across to home owners can be a real challenge, most want their homes serviced safely every bit as much as commercial property managers. It is a matter of taking the time to explain why you need to work in a particular way to stay safe and on the right side of the law.”

| Melbourne Health cuts OHS challenge down to sizeMelbourne Health has so many buildings across the Melbourne metropolitan area that it has its own postcode. And naturally, with so many buildings, there are hundreds of pieces of HVAC plant to serve them –and many are located on rooftops.So when Melbourne-based air conditioning firm Chillmech highlighted its concerns about the lack of safe access to service this equipment, Melbourne Health didn’t hesitate to begin rectifying the problem. Melbourne Health engineering coordinator Kelly Golmayer says a fall prevention audit of the buildings revealed the need for extensive works, which required a long-term approach.Carried out by Workplace Access and Safety, the audit identified numerous hazards, which were photographed, ranked and tabulated in color-coded summaries. “Each Melbourne Health site is governed by a committee and coordinated by a facility manager, which means literally dozens of people had to come to grips with the situation, the implications and what needed to be done,” says Golmayer. After submitting the audit to the various committees, and finding the budget required was unattainable, works ceased, and instead a list of priorities was developed with the assistance of Melbourne Health’s facility managers, including Cosimo Brisci.Works were scheduled based on the most pressing access requirements, and risk ratings were applied to each hazard.Now, more than two years into the project, the emphasis is on making Melbourne Health sites safe in a manageable process, without compromising the wellbeing of staff, visitors and patients. “Melbourne Health’s strategy of conducting audits to uncover the full situation, developing a manageable budget and works plan, and then reviewing their progress is textbook,” says Workplace Access & Safety managing director Carl Sachs.“Best of all, they’ve proven it works.” |

THE HIERARCHY OF CONTROL

The hierarchy of control is written into Australia’s fallprevention laws.

It highlights that the best outcome for a service technician is elimination. In practice this means working at ground level or on a level platform with a guardrail for protection.

The least preferred outcome under the hierarchy of controls is the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as harnesses attached to anchors.

Of course, the safety of these techniques is highly dependent on the method of fixing to the roof, user skills, mandatory maintenance and inspection of equipment such as anchors, and procedural controls such as rescue and induction.

“Apart from slowing down the work, often this means two technicians, with one of them trained in rescue, which can be really costly for the client,” says Sachs.

Building owners remain partly responsible and liable for the safety of the technicians, and cannot contract that responsibility out.

It is surprising to find, however, that there is no licensing or training requirement to fabricate or install safety equipment like anchors, static line, ladders and platforms, even though these items are classified as plant.

“It’s up to the building owner to make sure they get the safe equipment they expected,” says Sachs. “My personal advice is to seek independent third-party certification of the equipment’s performance.”

Sachs says schemes like NATA (for testing), StandardsMark (for Australian Standards compliance) and CodeMark (for BCA compliance covering installation) can be good tools to differentiate between conforming and non-conforming safety products and services.

“When building owners are presented with hazards and solutions in a factual manner, they generally fix it,” Sachs says. “They don’t want a death or serious injury on their site. But because they don’t get up on their roof, the need for the correct equipment has to be properly communicated.”

THINK BEFORE HOOKING UP

Sachs says anyone expected to work at height should not be afraid to speak up and talk to the facility manager or building owner about their safe access concerns.

“The best gear in your toolbox for working at heights is your site-specific safe work method statement – or SWMS – and your ability to ask questions,” he says.

“Everyone should spend 10 minutes writing one before starting work. A well-written SWMS or risk assessment is also great basis to start a discussion.”

Once you have worked through your SWMS, you are then in a much better position to decide whether other equipment is needed to get the job done safely. Sometimes this might be a harness – but often there are safer ways to do the work.

“The laws say we must assess risk and look at control measures first,” Sachs says, “not just put on the harness.”

Just because an anchor is there doesn’t mean it is capable of restraining you in the event of a fall. Recent testing has indicated that some roof-mounted anchors are not capable of restraining 100kg weights falling 2m.

“Air conditioning mechanics should not hook onto an anchor without asking questions,” warns Sachs.

“Given that plenty of us kitted out with tools weigh in at around 100kg, it is worth checking the testing and certification of the equipment that is designed to save your life.”

* This article was originally published in HVAC&R Nation – www.hvacrnation.com.au